This is a special Side-Quest edition of A Chemical Mind, where we leave the world of Medicine, Chemistry and Neuroscience entirely for one brief moment, to look at some random part of the universe, either from my own reading or experiences.

Today, I have a personal experience one for you: my memory of what it’s like to survive one of history’s most powerful natural firestorms.

Note: Check out the audio edition for a special format, including an original mini-soundtrack made for this episode!

A Pine tree doesn't burn.

It vaporises.

Eucalyptus - Australia’s Native tree - is explosive in its own right, but they’ve got nothing on Pine, which can suddenly flash-ignite, creating instant flame the entire height of the tree, as though the air itself was on fire.

Now try and imagine hundreds of thousands of densely packed pine trees, stretching for tens of kilometres, abutting a suburban street at the edge of a capital city, in the midst of a drought that had been going for years leaving everything bone-dry.

I'd just closed the back of the car after throwing in our evacuation stuff and looked up. The sky that had been pitch black minutes before was now red.

Furious, malignant red.

The smoke was rushing over my head at a speed that seemed impossible. The air was thick with ash and embers. My hair was covered in soot. My eyes stung.

I was living a reality I could never have imagined when I woke up that day, and it was only 3pm.

Little did I know even then that it would become a new normal for the country. Despite the utterly unprecedented power of this firestorm, having shattered our understanding of what should have been physically possible, literally forcing a complete re-write of every textbook on fire behaviour from then on, this would not turn out to be the freak once-in-a-century event we had been naively calling it.

6 years later, Victoria would experience Black Saturday, 8th February 2009, which killed over 140 people.

So much of what we've seen happening more and more regularly here in Australia, and in places like California in the USA, and in Canada, over the past 21 years since that day, really began in earnest here. Australia's National Capital.

That day, the Earth unleashed her full force upon humankind, showing us that there is a price to be paid for our greed.

The morning of 18 January 2003 was like most I had known since we returned to Australia: hot and dry. The lack of moisture in the air made almost any level of heat bearable. One could sweat it off.

None of us living in Canberra really understood the complaints of our Melbournian or Sydney-side cousins about 30°c. That was nothing in our bone-dry air.

Summer in Australia is often marked by days of pale smoke haze hanging over populated areas from the great bushfires that would burn many kilometres away from any major city or town, out in the deep bushland and national park areas. As for the bushfires, we're not known as the Sunburnt Country for nothing. You learn to expect them every summer. In fact, you’re distinctly surprised when they don’t happen.

Our native elders, the Aboriginal People, have known and cared for this land for 30,000 years. Fire has always been a necessary part of the cycle of life, clearing out old and dead biomass, releasing nutrients, and clearing way for new growth.

Life. Death. Renewal.

Rarely in Australia's history has a bushfire ever struck at the populated city centres, which are few and far between. Australia is utterly enormous in size, with a population today of only just above 25 million people, most of whom live in the Eastern coastal cities of Melbourne, Sydney, and Brisbane. Its capital, Canberra, is perhaps the most inland city, some 2 hours drive from the nearest coastline.

It was summer school holidays, so I went out to see friends. We talked about the faint white smog, the fires in Namadgi National Park, and girls (Jessica Alba was the muse of my male friend group). The smog early on in the day was pretty light. Some summers, the air could be thick with the stuff.

No one felt under threat. A bushfire had never had a direct hit on a city like Canberra in our nations long history of natural disasters: as far as we knew, there was no reason for one to hit now, either.

But there was. In fact, there were several, all coalescing together. We just didn't realise it. No one did until it was far too late.

Around about 1pm, I'm making my way home from Woden shopping centre, only 5km away, when I see it.

The most enormous pitch-black cloud hung over the westerly sky, in the direction of home.

The image is burned in my memory.

You cannot forget something so surreal. The air was already full of white smoke, yet this black cloud, as black as a void, stood out in that scorching sky like a terrifying threat. Like God himself was screaming at you to run, to turn back now.

I had to get home, so I got on a bus. You could feel it now, among the passengers, the driver, the people on the street. This isn't how it was supposed to happen. Weren't they supposed to have it under control? Fires don't come down this way, it's just not the way of things.

I got off at my stop and rolled on my skateboard to the house. Mum had the hoses going. Above us, the black void opened its jaws and swallowed the Sun, killing it almost instantly. A faint red glow existed briefly where it used to be, before it, too, was snuffed out.

ABC Radio was on, the TV also on the ABC. Up until now, the messaging had been clear: there was no threat to the city from this fire, despite it jumping containment lines, despite the wind blowing directly Eastward (towards us), despite the charred ash and small embers that were beginning to fall on us.

None of us knew the black mass of smoke was a product of one of the most explosive natural firestorms in recorded history, produced when the 4 major bushfires which had been burning in our great national parks for weeks made contact with the tens of kilometres of thick pine forest and merged to become a single fire front.

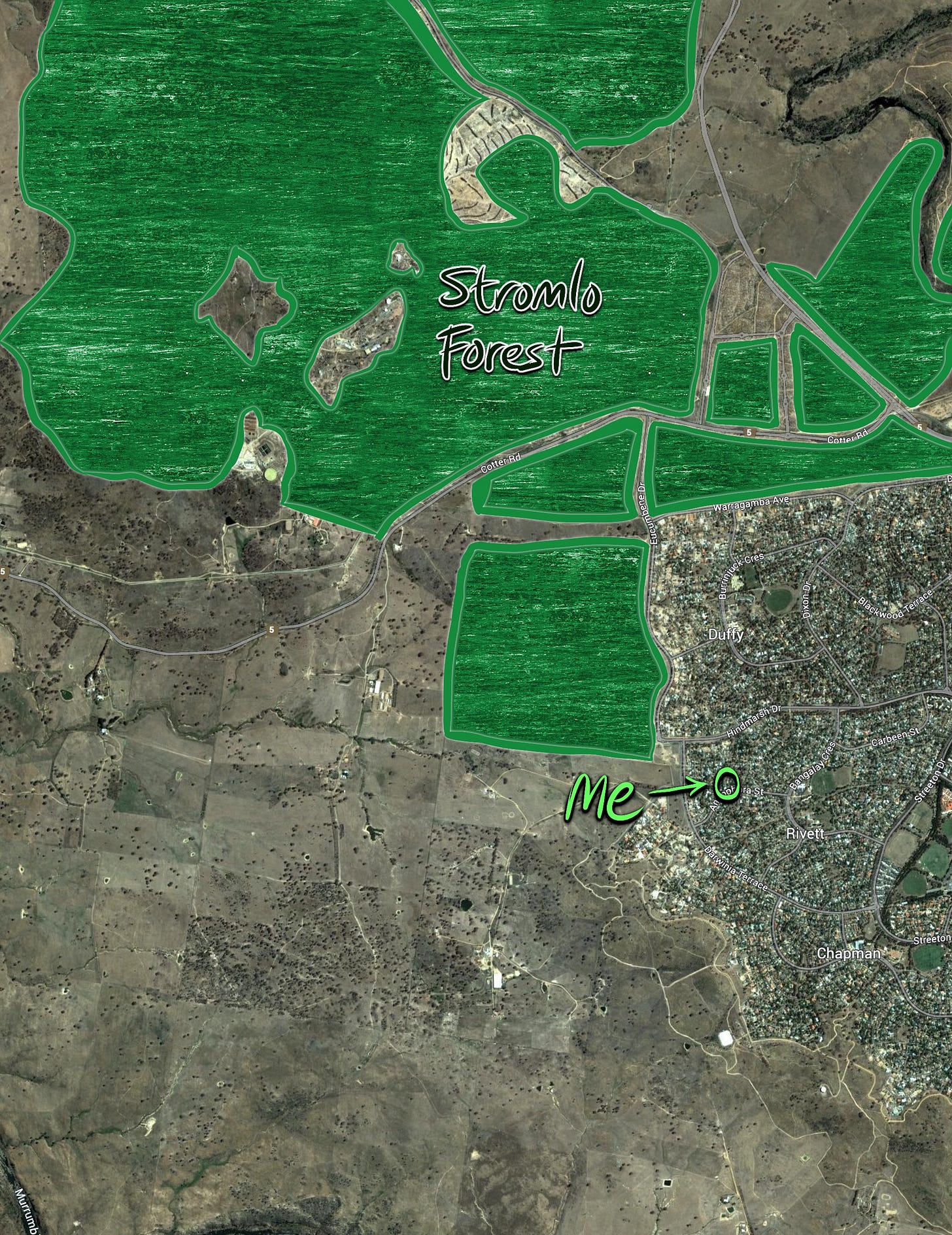

Rivett is a smaller suburb sandwiched between Duffy and Chapman. Most of my friends lived in those two neighbouring suburbs. The utterly enormous Stromlo Forest, a plantation of mature and giant pine trees, stretched for some 60km to the west, with the tree-line directly abutting our 3 suburbs, separated from the houses by a single 2-lane road, no more than 30 metres.

I knew that forest well. I had spent many, many days riding my mountain bike along the many dirt tracks that cut between the trees. It was a place where sunlight never touched the ground, the tree cover was so thick. Years worth of fallen pine needles littered the forest floor in a brownish mush, sometimes making deep piles.

At the top of the hill, deep within the forest, was the famous Stromlo Astronomical Observatory, a place my father used to take me to visit sometimes.

By this point, the enormous telescope at the top of that hill was already burned to the ground.

I got up on the roof of the house to hose it down and looked to the north in the direction of Duffy. It looked like the whole suburb had been absorbed into the cosmic void. Consumed by divine rage. New shoots of black rose as it progressed ever forward like a pyroclastic cloud.

No one had been prepared for this. Bushfires simply don't move that fast. We thought we had time. We thought it would take another few days to cross the tens of kilometres distance. We thought it would be stopped long before it reached us. We said as much to ourselves right up until the polytonal siren that marks the Emergency Alert System's bone-chilling wake-up call.

It wasn't until 3pm - a bright and sunny afternoon overturned by a midnight darkness - when suddenly the TV flashed to the Emergency Alert System broadcast.

Although it's been over 20 years since then, and no recording of the television version of the alert is available, this is what it sounded like on the radio.

Then, the power went out.

“It was a bit of a shock. There’s nothing in the literature which suggests a fire should spread that fast, or could spread that fast.”

Dr Jason Sharples, UNSW

The sound of a bushfire at full tilt is like if thunder were continuous. It's not the sound of the wind, though the wind was at gale-force already.

It's the sound of hundreds of thousands of years worth of tree life being converted into energy, by way of a chemical reaction. It's the sound of rage, pure and visceral, from the depths of the Earth herself.

The smoke from the fire formed dense pyrocumulus clouds - normally caused by volcanic eruptions - that became electrified, creating lightning. Oxygen was being burned up so fast, it caused more air to rush in to the fire system at gale-force, from all directions.

Every 10 seconds, more energy was being produced by this fire than the 15-kilotonne atomic explosion in Hiroshima.

Every 10 seconds, another atomic bomb’s worth.

6 bombs every minute.

60 bombs every hour.

In its all-consuming rage, it spawned a brand new monster: a Fire Tornado.

Such an event had never been recorded, or seen, by human beings before. It had not even been thought possible. Yet, there it was. Rated an EF3 on the Enhanced Fujita scale, it uprooted trees right out of the ground, picked up police cars and trucks and dropped them kilometres away, and left a trail of destruction in its path.

Mum and I knew we had to get out. There was no point holding ourselves hostage to the vicissitudes of this unfolding catastrophe.

Luckily, we had long practised a drill, summed up as follows: "how to get the fuck out in a big hurry". We grabbed only 2 things: the box of important documents - birth certificates, house finance documents, etc - and the desktop computer tower. We’d chuck them in the back of the car and go. If we could, we’d get the cats in the carrier and take them as well.

We couldn't find the cats. They were outside cats, and we just had to pray they would be alright.

As we were getting in the car, I looked straight up above me, and I will never forget seeing the red and gold light of flame reflecting off the thick black smoke as it raced above us at speeds I could barely comprehend. My eyes began to sting from the soot, so I took one last look at the house, and wondered if we would ever see it again.

Things can be replaced. Lives cannot.

So we fled.

Worried waiting

Fire crept over Mount Taylor as I watched from our Evacuation Point - a friends house in Torrens, only a few kilometres further in to the city. The power was out, and there wasn’t much to do but watch, and wait, and hope we wouldn’t have to evacuate again.

We were safe that night, because of the heroics of our incredible, incomparable emergency services fighting the blaze that day, many having been fighting it for weeks as it made its advance towards the outskirts of the city.

When night fell, conditions eased somewhat, allowing our exhausted firefighters a desperately needed reprieve; time to catch their breath and shore up the lines.

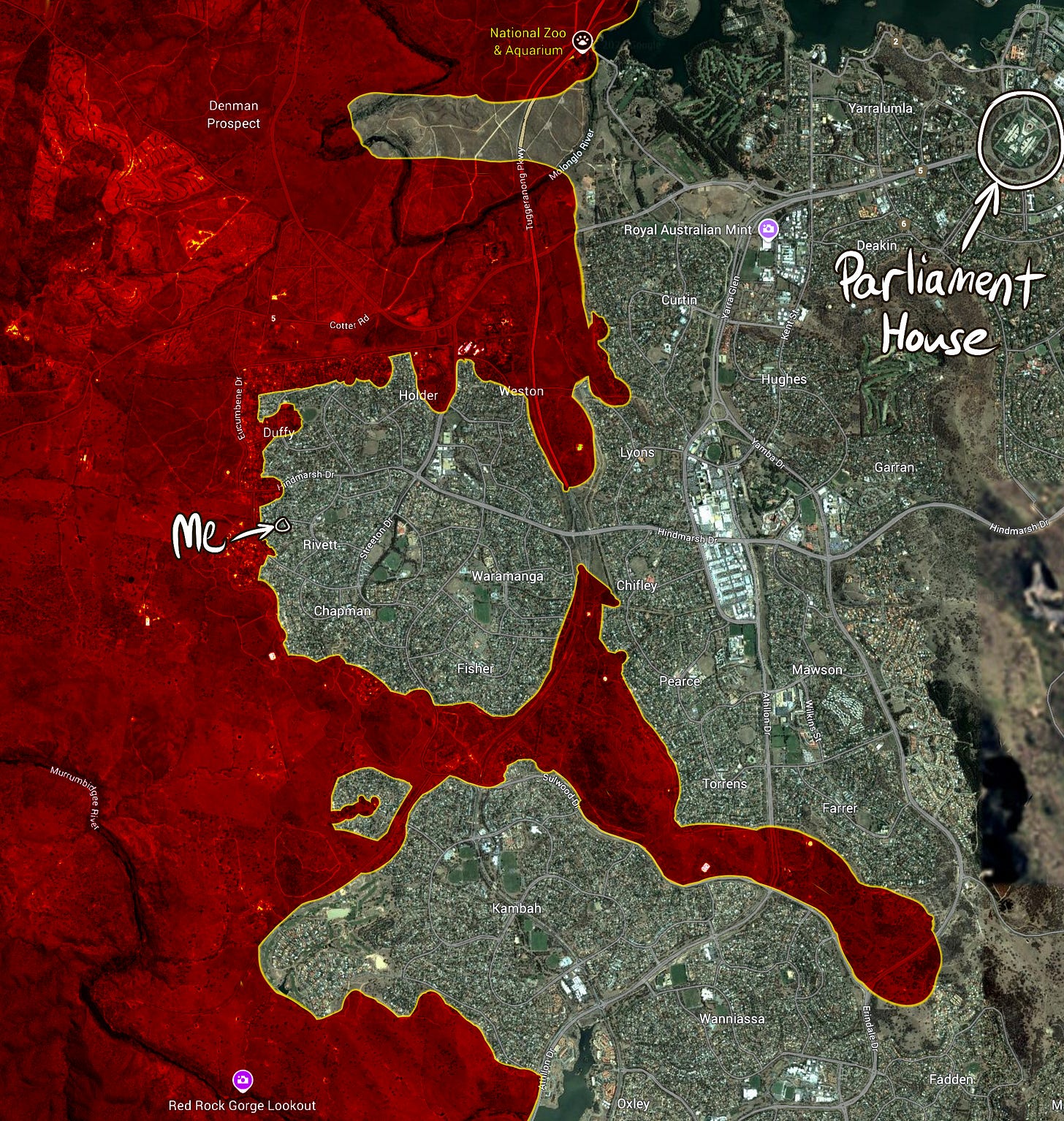

By that point however, the fire front had already pierced the very heart of Canberra.

Parliament House, standing like a capstone at the centre of this planned city - the locus of Australian political power - was separated by no more than a few kilometres from the raging inferno.

Little Red Tulip

Days later, the fires were finally brought under control, having burned through most of the available fuel. It was deemed safe for those who had evacuated to return and survey the damage, hoping against hope that maybe - just maybe - they still had a home to return to.

We drove slowly and carefully up our street. The white ashy smog wasn’t as thick as it had been, but its presence was undeniable. Ash and detritus littered everywhere. Burnt patches the sign of small spot fires in grassy front yards. So far, coming from the East side, no burned-out houses.

We came up on our house.

It was still standing. Surprisingly, so was the front garden: more or less untouched by any spot fires which - had they managed to take hold - would almost certainly have had more than enough fuel to destroy everything.

We pulled the car onto the blackened and grey dust-covered drive way, the crunching sound of the ash and tree bark beneath us like the groans of party guests still hung-over from the night before.

As mum went inside to check the state of the rest of the house, I decided to walk a little further up our street, to see where the fire front was halted. It didn’t take long to find.

It had only been 4 houses away.

The often surprising thing about even the most ferocious bushfires is how selective they can be. An entire street could be decimated, save for one or two houses, inexplicably left right alone. Sometimes it would take just one or two houses in a street, but otherwise bypass it almost completely.

However, for most of the area of fire damage, it was near-total destruction. Few houses which lay within the fire’s final path were spared. The entire suburb of Duffy just next to us had been utterly transformed, from a leafy-green middle-class slice of suburbia, into a simulacrum or photocopier reprint of the surface of the moon.

When I reached the top of my street, I noticed a house on the corner whose front yard - which had previously been a well-kept garden with native trees and colourful flowers - was reduced to an uneven pile of black ash.

Yet something caught my eye.

The tiniest splash of colour.

I moved closer to inspect it.

Sitting amongst the black ash, apparently untouched, was a single bright-red Tulip.

Everything else in that yard - the grass, weeds, flowers, trees, everything - had been thoroughly burned down to a pure black ash, yet this one flower remained utterly undisturbed by the maelstrom.

Despite its entire world ablaze all around, it stood tall, face turned to the Sun.

An act of defiance against impossible odds.

I’ve spent my whole life since then trying to be more like that little red Tulip.

Aftermath

When the last embers were finally extinguished, the damage was counted. 400 homes destroyed. Another 500 significantly damaged. $1 billion worth of destruction. 4 lives lost.

It was considered to be just a one-time freak event, until Black Saturday struck in Victoria only 6 years later.

This was the beginning of the age of firestorms, fuelled by a changing climate and year after year of record-breaking temperatures. First we had 2003 setting the record for the most extreme fire event in our history. That record was broken in 2009 during Black Saturday. Then, it was broken again, multiple times, during the 2019-2020 fire season, now known as Black Summer; at one point, 3 states had declared a fire emergency at the same time.

Things have been relatively quiet on the bushfire front the last few years, but we know that cannot last.

The firestorms will rage on.

Did the cats make it?

What a hair-raising story.