Emperors of Maladies: Augustus

How a kid with chronic illnesses and his best friend conquered Rome and shaped history

Before we get started…

I’ve updated BlockedStack, my Substack Browser Extension, with the ability to export all your Substack notes that you’ve ever posted and download them all into a single giant Markdown text file. Give it a try! Available for Firefox and Chrome.

Now, on to today’s article. Enjoy!

In late 2018, one Mark Zuckerberg got a haircut, something which made a lot of people on the internet very angry, and has been widely regarded as a bad move.

What’s wrong with haircuts?

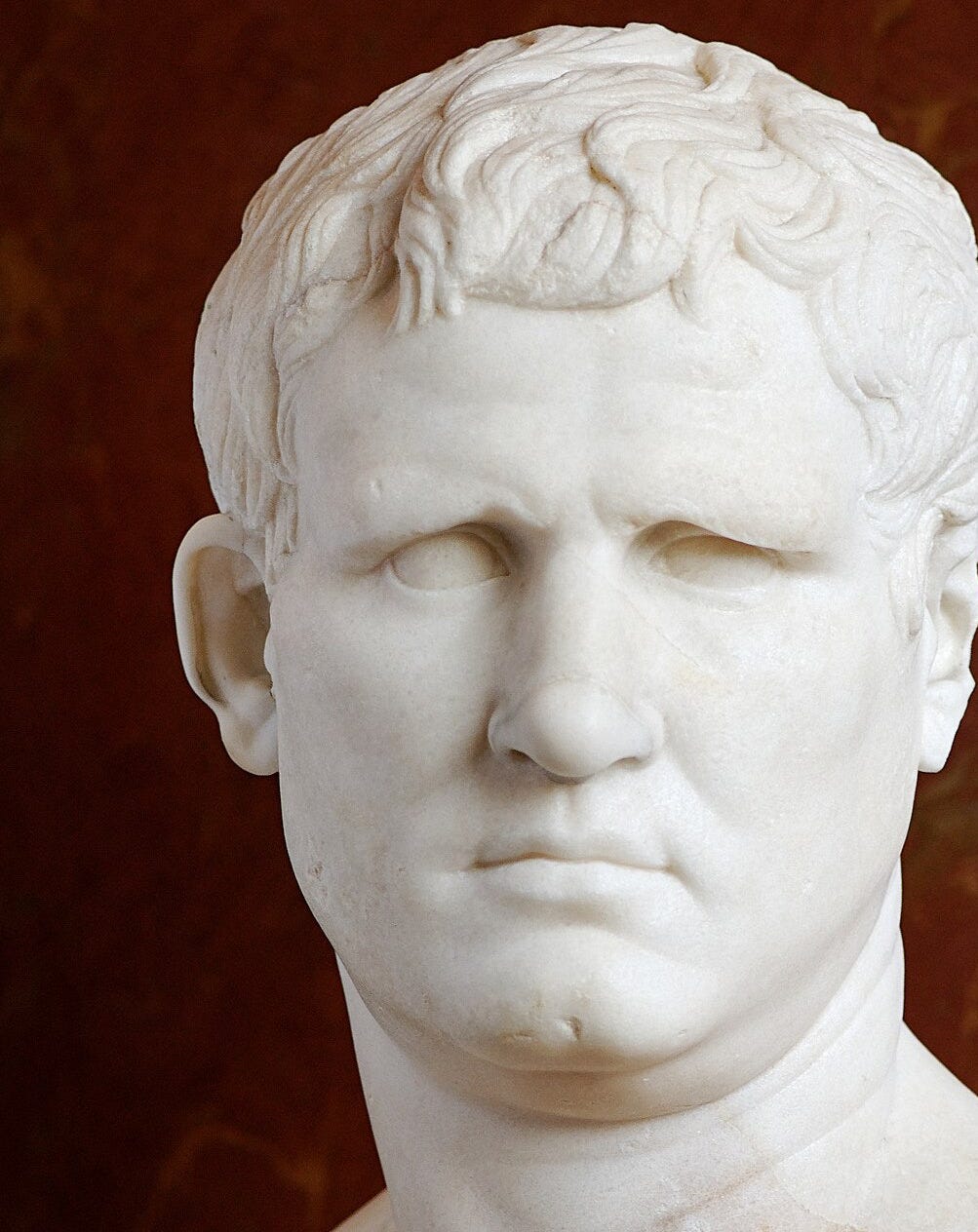

Well first of all, it didn’t seem like a particularly good haircut (and profoundly rich people only get the best haircuts), and second - according to internet historians - it looked strikingly similar to the haircut on some ancient statues of Augustus.

You know, the Roman Princeps, adopted son of Julius Caesar, the kid that overthrew the Roman Republic and replaced its peaceful, all sunshine-and-rainbows democracy with a dastardly evil Empire? That interminably blood-thirsty psychopath who once appointed a horse as head of government? (That last part wasn’t Augustus, actually, that was Caligula, but the way journalists were talking about him, it might as well have been!)

Well, apparently, our boy Zuck here has a certain fondness for Augustus, and he and his wife spent their honeymoon checking out relevant historical sites around Italy. So, naturally, given the fact that the Romans were also fond of cutting their hair every now and again, the implication was clear: Mark Zuckerberg believes he IS Augustus, Supreme Roman Dictator, Princeps Metamaximus!

Once this connection was made - between a haircut and a Roman emperor - the news media ran with it so hard.

It was one of those occasions when one can only assume it was a slow news day, or perhaps week. Suddenly, a whole lot of nonsense non-stories started spewing forth from respectable publications (and otherwise), all at once, all casting shade on my boy Augustus.

I have no fondness for Mark Zuckerberg, let’s just be clear on that.

I have even less fondness for autocrats and dictators. (If you’ve been following me for any appreciable length of time, you would know this.)

However, I do have a certain fondness for Augustus in particular, and it’s not for any of the reasons you might think.

Trust me. In order to explain, we’re going to need a fair bit of context.

What was the Roman Republic?

The idea that any state could go from a “republic” to an “empire” makes it seem like it must necessarily have been a democracy overthrown by some evil regressive autocrat, but this was unlike any democracy we would recognise in today’s world.

The fact is, the Roman Republic was an Oligarchy, albeit a kind of elective one.

Rome was neither a direct nor an indirect democracy, and had no such pretensions. It had no elected legislative assembly composed of the people’s representatives, and no ideological political parties that competed for power.

The voters did not choose between a failed leader and a successful one, or between one political platform and another, but between candidates who were all drawn from a select group within the citizenry which held the exclusive right to compete for the various positions (ius honorum) in line with a set of rules established over the years by both tradition and legislation.

Roman Elections in the Age of Cicero, by Rachel Feig Vishnia (2012)

Although the system was better at self-correcting than the Empire would be later, and was still more representative at the end of the day, it was not by much. It was also viciously aggressive, expansionist, and imperialist beyond anything the Roman Empire itself would ever be.

For its entire 482-year existence, it had spent 466 of those years at war; as such, the famous doors of the Temple of Janus - which were kept open during war, and closed during peace - spent a measly 16 years closed prior to Augustus. Most of Rome’s wars were of conquest; though this is quite possibly one of the reasons the Republic managed to survive for so long.

So this idea that Augustus replaced sunshine-and-rainbows democracy with aggressive imperialism is outright nonsense.

At the same time, there really is no answer to the question “Was the Roman Empire a good thing?”

It was just a thing. It existed. It had a profound influence on the world, both in positive and negative directions. The weight of each of these influences will differ from person to person. They are necessarily subjective, and our assessment of it is not only limited by the historical records which have survived and what archaeology manages to reveal, but it is also tainted by the context of our own times.

Up until relatively recently, Empires in general were commonly seen as civilising forces for good in the world. Today, however, we know all too well the harm they are capable of.

Okay, great, so how does Augustus fit in to this story?

I’m getting to that!

Gaius Octavianus (a.k.a Octavian), later known by his adopted name Gaius Julius Caesar, and then later by the name Augustus (but we will call him Octavian for now), was just 19 when he first set out from the military camp in Illyria - where he had been training - over to Italy in order to learn the contents of his great uncle’s will. His great uncle, of course, was the one and only Julius Caesar, who had been assassinated on the Ides of March.

Since Julius had no legitimate children, he had adopted his nephew Octavian as his own son - as was common practice in Rome - posthumously, bestowing to him via his will (kept safe by the Vestal Virgins) all his wealth and property, but most importantly: the name of Caesar.

That name was the equivalent of a super weapon in the Roman world by this point. It gave Octavian instant legitimacy among the Roman army, plus the instantaneous and total personal loyalty of Julius’ legendary veteran legions, those that had been with him throughout the conquest of Gaul: the “Caesarians”.

All of a sudden, this province-kid’s life went from normal Roman province-kid stuff, to being the inheritor of all that was Julius Caesar, at the very moment when the Republic itself was imploding.

In Roman politics, military glory was everything.

No, really. I don’t think you fully understand, so allow me to emphasise: EVERYTHING.

If you wanted to have a political career in Rome, to leave your mark on society and on history, you had to get out there and lead some troops into battle. It didn’t matter who you fought or why you were fighting them, you simply had to fight and win, and be seen to win - or, at the very least, have someone write that they saw you winning.

Julius had managed to pull off a fairly spectacular political career for the time, before making a real name for himself on the battlefield, and this was a feat of its own; he made very smart, very timely alliances with all the right people, riding up with them in power and prestige. After a stint as Consul, however, and some serious political defeats (he became very unpopular among Senators for having several of them beat up by street thugs for opposing him), he was effectively exiled away from Rome’s centre of political power, and made Governor over the border province of Transalpine Gaul.

Being governor of a border province was the traditional way that men could build power, status and personal wealth. They were typically assigned a certain number of legions - the standard unit of the Roman army, like a division - who were supposed to assist in “maintaining order” in the province.

Instead, what they usually did with these legions was to expand the borders of Rome, by invading and conquering neighbouring territories. This could be a brutal process, to varying degrees. Most of the time, after defeating whatever resistance there might have been, instead of simply slaughtering all the people that had been living on those lands, they would be assimilated as Romans; although much land would also be confiscated and redistributed to the families of the troops.

The tricky thing is: this was technically illegal under Roman law. You could be charged with very serious crimes. Nevertheless, as long as you were outright victorious - successfully expanding the borders of Rome and subjugating any and all peoples in the way - everyone would simply forget about trifling details like the illegality of the act; furthermore, you were likely to be granted a Triumph: a massive parade through the streets of Rome herself, where you would be painted up to represent Jupiter Optimus Maximus, King of the Roman Gods, and driven around in a grand chariot with all the slaves and booty captured in your conquest marched along behind.

If you were not outright victorious; even worse, if you lost territory; and even worse than that, if you actually survived: your name would be tarnished, whatever fortune you may have had would be decimated, and in the political climate in which Caesar was living, you might even lose your life.

In Rome, the ends justified the means.

Existential Dread

For a long time, Romans had an unusually visceral, even primal, fear of barbarians. Not just any barbarians, but one very specific group of them: they were called the Gauls.

Roman mothers were said to use that fear as a way to straighten out naughty children: “You better behave, or else the Gauls will get you!”

This fear stemmed from the one time that Rome herself was ever completely overcome by an outside force: the 390BC Sack of Rome by a Gallic warband. Rome’s great Legions appeared utterly impotent against them. The Romans never forgot, and never forgave.

So, in this context, becoming governor of a province up alongside the borders of Gaul - more commonly known today as France - with a mere handful of legions was probably not an ideal scenario for those seeking easy victories.

Julius Caesar, as noted earlier, was not exactly known for any special military prowess at this point, either, and the Gallic tribes were thought to have some of the best warriors in the known world. It turns out, however, that Julius understood tribal armies the way most Roman commanders did not: he realised they are easily divided, and thereby more easily conquered piecemeal.

Divide and conquer.

So that’s what he did: he marched into Gaul, and arranged things in such a way that he could fight one tribe at a time. It was a strategy he employed with ruthless efficiency, and within 4 - 6 years, he had conquered the whole of Gaul - a territory spanning today’s Switzerland, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxemberg - and had even made initial excursions into the British isles.

Yet it was not simply the conquest itself which made Caesar the most powerful name in the history of Rome; it was the fact that he himself wrote the history of it, in letters he sent back to Rome, regularly chronicling his exploits in heroic and vivid imagery. Caesar was a propagandist of genius, and his “Commentaries on the Gallic Wars” was then and is still today considered a master work of written Latin.

The Roman people were enthralled by Caesar. Ultimately, his name would become immortal in ways that even he could never have imagined.

Rubicon

Julius Caesar did eventually return to Rome under threat of arrest and prosecution for his conquest of Gaul - something which had almost never happened before to a victorious General - and in order to protect his name and legacy from ignominy and exile for political ends, brought one of his legions with him, which by definition was an outright act of treason and declaration of war on the Roman state.

This lead to the civil war, which Julius won with great skill, and great tact; he made a point to show clemency to many of his enemies, especially those he defeated on the battlefield. He would offer them amnesty, and try to recruit many of them to join his administration. He let most captives go free, even when he knew they intended to fight him again.

He refused to emulate victors from previous civil wars in Rome, who had famously drawn up lists of their opponents and people they disliked in order to have them rounded up and executed in an orgy of violence and bloodletting.

Nevertheless, although Caesar stood victorious at the end of the civil war, and had gone out of his way to prove himself virtuous, compassionate and trustworthy, he did not turn down the copious honours, rights and extraordinary powers the Senate showered upon him.

Yeah, rookie move. When you’re trying to be an emperor, you’re not supposed to look like you’re trying to be an emperor.

His face began appearing on new coins, something which had never been done before. He sat atop a throne in all but name. He wore Royal colours. The only thing he turned down was a literal crown.

It naturally freaked out a bunch of people, including several young ideologically-charged senators, who decided it was time for a bit of good ol-fashioned Tyrannicide.

It was carried out on the Ides of March, and the great Julius Caesar, Conqueror of Gaul, Dictator of Rome, “tyrant”, was dead.

Et tu, Bruté?

Now we return to Octavian, our future Augustus (he wasn’t yet known as Augustus); he was also not known for any special military prowess, and in fact was too young to have commanded troops into battle; yet with the name Caesar, he was warmly welcomed by the old Caesarian veterans when he arrived at a garrison in Brindisium. That was the power of the name alone.

At the time, it was assumed that Mark Antony - Julius’ right-hand man who had been by his side throughout the conquests and the civil war - would take the mantle of Caesar and assume power. This is, in fact, what Mark Antony had believed as well, and upon finding the body of his leader on the floor of the senate, carried it out to the public square and proclaimed his iron determination to bring the murderers to swift justice.

When the young Octavian shows up, bearing Caesars last written will and testament, which stated clearly who the true heir to Caesar was, things became… complicated.

Mark Antony was a capable military man, who had been steeped in blood and victory for most of his life. He had also spent time in charge of Rome when Caesar left Rome to chase down the last remaining resistance (and then got “distracted” by a young Queen Cleopatra of Egypt).

His time in charge of the city, however, was nothing short of catastrophic and scandalous. He was drunk throughout most of it, mis-managed everything, screamed at everyone, and letters were sent by people of Rome to Caesar in Egypt begging for his return, to save them from Antony.

Octavian, on the other hand, would turn out to be an intelligent and diligent administrator, a brilliant and subtle politician, and a very, very good friend.

Friends Forever

Something you learn from reading a lot of Roman history is that powerful people don’t really have good friends, because those that do are all too often either usurped by them, or will become so paranoid about such an eventuality that they will end up destroying everyone. See: Justinian and Caligula, for starters. There are few examples of total and unmitigated loyalty and devotion between someone of supreme power and any other human being, especially when unrelated by blood or marriage.

However, Octavian (Augustus) had a most loyal and most capable best friend in a man named Marcus Vipsaneus Agrippa.

The friendship between Octavian and Agrippa was something so special, that it is difficult for me to recall an example like it in history, though I know there must be some.

They first met as boys, and bonded quickly. The teenaged Agrippa followed Octavian to his first and only meeting with his famous uncle Julius Caesar, and trained alongside Octavian at the camp in Illirya. When word was received about the events of the Ides of March, Agrippa was steadfast in his support for Octavian, agreeing to assist him in whatever way he could.

Octavian needed the support: he was chronically ill throughout his life, afflicted constantly with severe gastrointestinal problems, migraines, a skin condition, and much else besides including several close brushes with death. This often prevented him from being able to command his own legions in battle; a story is retold by Suetonius in his “Lives of the 12 Caesars” that, on the moment of engagement during one battle against Antony at Actium, Octavian was hit by severe abdominal cramps which forced him to the ground, and he had to hand over command to someone else.

He had miraculously managed to escape death in camp another time, after leaving his sickbed shortly before it was unexpectedly overrun, his tent being stabbed through by enemy soldiers believing he was still there.

As such, he often had to hand over military control to others in moments of crisis, when even his own body rebelled against him.

This would normally be a very dangerous thing to do for anyone seeking supreme power: victorious generals often gained the loyalty of the legions they lead, no matter who was supposed to be in charge.

However, Octavian was not the typical political power player, and he had an incredibly competent and capable man whose loyalty was without question on whom he could rely.

It was during the Civil Wars that broke out between Antony and Octavian that Agrippa’s genius for military tactics first came to the fore, both on land and at sea. Octavian, lying in his sick bed, doubled over with cramps, handed command to his friend, and charged him with dealing a decisive defeat to Mark Antony once and for all, at Actium.

It was quite possibly the best decision of his life.

Agrippa had already smashed the Naval forces of Sextus Pompey at Naulochus, in 36 BCE. This time, he was up against the combined navies of Cleopatra and Antony himself, with forces that were roughly equally matched on both sides.

Yet, he was unstoppable: Agrippa routed the enemy decisively, causing Antony and Cleopatra to flee for their lives. Antony later killed himself (thinking that Cleopatra had already done so, but she was captured alive.)

Every victory that Agrippa stacked up was a victory for Augustus, and every attempt at honouring Agrippa was politely turned away and redirected toward his friend. As the Principate became established, with Octavian - now Augustus - in supreme power, he showered Agrippa with titles, positions of honour, tasks of the greatest importance to the state. Agrippa became the one he turned to in every crisis, knowing there was no better man for the job, no matter what it was.

When Augustus famously said “I found Rome a city of bricks and left it a city of marble,” most of this enmarblification was carried out by the indomitable Agrippa. He consistently ensured things got done. One of his many, many infrastructure projects was the repair and maintenance of Rome’s main sewer system, the Cloaca Maxima - it’s still in use to this day.

Agrippa applied his talent for assessing a problem, determining the solution, bringing together the required resources and then getting the work done.

Marcus Agrippa: Right-hand Man of Caesar Augustus, by Lindsay Powell

Augustus had been so sickly for his entire life, that it was assumed he could not possibly out-live most of his friends. Only 12 years following the smashing of Mark Antony and Cleopatra’s combined fleets at Actium in 31 BCE, Augustus became convinced of the need to ensure the succession of the Principate - the word used for his position of great power in the state, chosen deliberately to avoid anything resembling monarchy - and that there was only one man on Earth he could entrust such a responsibility to: his best friend.

Thus, he elevated Agrippa once more, this time placing him - politically at least - on equal footing to Augustus himself. Should Augustus die, Agrippa would carry on.

Yet, in an unexpected twist of fate, it was Agrippa who would die long before his friend took his last breath. Few things in Augustus life devastated him so much as this loss. Cities and towns all across the vast Roman lands raised monuments to the memory of Agrippa. The people had loved him for all the work he had done to build and repair public amenities, roads and infrastructure, all across the land. Augustus minted so many coins bearing the profile of Agrippa, that they circulated throughout the Roman world for a very long time, and are today a common collectors item. Augustus wanted to ensure the continued memory of his best friend.

Agrippa was not forgotten.

It can honestly be said that this duo was one of the most significant friendships in all of human history. Between the two of them, they defeated their enemies in the civil war, and proceeded to conquer the hearts and minds of the Roman people.

Together, they created a legacy so enormous, so overwhelming, and so enduring, it has stood tall like a beacon of achievement for over 2,000 years.

I’ve not heard great things about Mark Zuckerberg’s ability to form close relationships with others. Like most men of power and wealth, he seems to enjoy standing alone. His creations might also one day be regarded as a net-negative to society in general, having helped to foster much polarisation and division, rather than unity and shared values.

In these and many other ways, he is nothing like an Augustus, not even with a bad haircut.

This is Part 1 of a 2-part series, profiling two very different people in supreme power whose illnesses and disabilities had profound impacts on world history. Next, we’ll be taking a look at one Kaiser Wilhelm II, and how the black sheep of the family with insecurities beaten into him, and only one properly functioning arm, was forever branded by the world as a warmonger, when he was nothing of the sort.

See you then!

Amazing article. Loved every sentence of it.

This was such an interesting read. Loved this article. Excited for reading the further ones!!

But why would be Mark Zuckerburg considered a net negative in future? I don't know much about him, except the fact that he created facebook. So, is it not a social networking site that bring people together?

Rest it was really really intersting :))